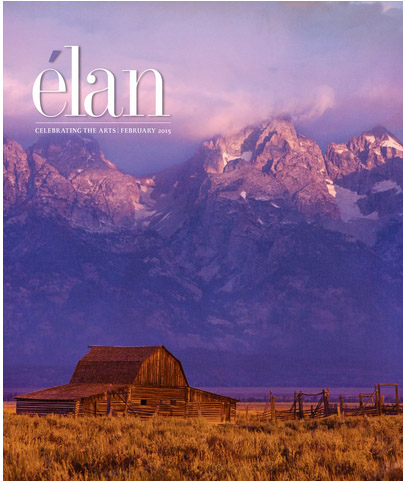

“Falling Light, Grand Tetons” Cover feature for the February 2015 edition of Elan Magazine

“Falling Light, Grand Tetons” Cover feature for the February 2015 edition of Elan Magazine

I sometimes hear “you have a good eye” when speaking to folks visiting in the gallery. They are being complimentary of course, saying that they like the subjects, find them interesting, and clearly are worthy of a picture. They might even have been emotionally affected by the photograph, an outcome every artist hopes for.

Making an emotional photograph requires so much more than the subject alone. It must also tell a story that moves people. Having a “good eye” isn’t nearly enough.

As humans, our eyes can see almost 180 degrees (a full semicircle) in front of us. There may be hundreds or thousands of distinct objects within that field of view, especially in nature. Including too many of them or putting them in the wrong position in the photograph will make it difficult to tell just what is going on.

Master photographer Ansel Adams once said “There is nothing worse than a sharp image of a fuzzy concept.” That was his way of saying that good photographs tell a clear, compelling story. And just like a literary story, the photograph must have a leading character –a subject– certainly, but it must also place that subject in context with other elements of the story in order to evoke an emotional response.

I think that telling a good story is the hardest part of creating art photographs. Sometimes the lighting isn’t right. Sometimes the colors or tones clash. Sometimes the rhythm is way off. Lighting, color, and rhythm are each important contextual elements that can either celebrate or belittle the best of photographic subjects.

I want to use “Falling Light, Grand Tetons” as an example of one approach to making an artful photograph.

A couple years ago I visited the Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming specifically to take pictures. One of my objectives was to capture a picture of the famous Moulton barn on Antelope Flats, one of the most photographed barns in America. A quick Google search illustrates how others have photographed this subject: Typical Moulton barn photographs

The image just below is an unaltered image of the scene that closely approximates what my eyes saw at the time. This view approximates what anyone would see if standing next to me at the time.

I saw a story in this scene. It was a story of human struggle on the high plains of the Grand Teton mountain range. The main subject was the old abandoned barn, dominated by the eternal, massive, menacing mountain range. To me, it was a story of humanity’s neverending fight with nature: in this case a battle lost by those who abandoned their homestead simply to survive.

But my story wasn’t being told very well in my first take. I felt my subjects were weak and not really as sublime as I wanted them to be. I needed to isolate the barn–my leading character–within the scene and make it appear more intimate with the mountains. So I changed to a vertical perspective and replaced the lens with a zoom lens.

Compositionally, I felt that this was getting closer to my story: the barn was now isolated from the surrounding visual clutter and the supporting subjects (the mountains and foreground) were in the right proportion. Placing the barn near the bottom of the frame supported an illusion of pressure and force of nature upon it.

But things still lacked a strong sense of desolation and hardship that was important to my story. The tension and sublimity I felt on site was missing in the photograph; my camera had failed to capture my emotions (as it always does). In other words, other contextual elements were not supporting my story. I knew I’d need to modify them for my story to be told well.

This image clearly needed help with the lighting, so dodging and burning was called for. Dodging and burning are techniques used to brighten (dodge) or darken (burn) specific elements or areas of an image to create an illusion of light and shadow. These techniques have been used since the invention of photography, and I use them often as I artistically interpret my photographs. Here I felt the barn (and therefore the foreground grasses) needed brightening to make it clear that it was the subject of the story. The mountains also required a bit of contrast boost to make them appear menacing and stark.

The final important changes affected the colors in the image to emphasize rhythm and visual depth. Warming the mountain peaks and the foreground accomplished both. The warmer foreground advances toward you, inviting you into the scene, and the warmer mountain peaks improves the illusion of them hovering (dangerously?) over the barn. I felt the final result told the story I wanted to tell about this famous barn.

Making successful photographs requires much more than having a good “eye.” Finding a great subject is certainly critical, but telling a story about that subject is so much more important. Not everyone will see the same story as the photographer. But this is true: if the artist tells a good story, it is much easier for someone else to emotionally engage in the scene and dream up their own setting, plot, or ending. And that’s what art is all about.

If you are an art photographer, here’s a trick I’ve found useful. Force yourself to title the final photograph before you click the shutter. Use a conceptual title, such as “Falling Light”, “Fight with nature”, “desolation and abandonment..” or whatever reflects how you feel about the scene before you. Once done, you have a concept about the story you want to tell. That concept will then guide you as you compose and interpret the scene much better than a title like “Barn in the Grand Tetons” or “DSC12345678-1.”

Happy storytelling.